Journal Jottings

BOOKWORM

scribendi cacoethes

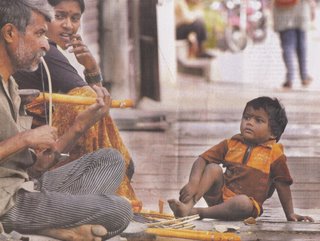

Heed my prayer...

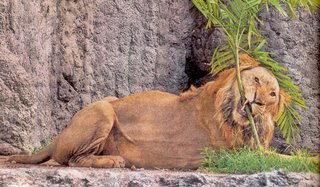

Will they survive the effects of global warming?

Hear my song...

At the Nehru Zoological Park, Hyderabad, white tigers wait to be 'adopted' by patrons.

See me dance...

Elvis, the young Blue or Fairy penguin, is fitted with shoes for his poor little callused feet.

BOOKWORM

[more about Rafael Sabatini’s short stories]

THE FOOL’S LOVE STORY ~ The Ludgate, June 1899

Through 1899 and 1900 Rafael Sabatini continued writing short stories and continued to experience the gratification of seeing many of his stories published.

With theatre in his blood, language in his marrow and his brain teeming with stories, Rafael Sabatini wrote many different kinds of story as the ideas came to him, being under no obligation yet either to earn a living or to please a particular readership.

The Fool’s Love Story has so many interesting points that it’s not easy to choose which one to begin with. So first, to clear away the least important, the fool or jester of the title is named Kuoni. In 1903 Sabatini’s first play was produced, under the title Kuomi the Jester. Nothing survives of it that has come to light so far, but it seems likely to the point of certainty that the play has this story for its plot. In parenthesis, Sabatini had an idiosyncratic way with the names of characters to which reference will be made from time to time. Here it suffices to note that the name Kuoni is repeated for a quite different character – a wholly evil court jester – in the lateish novel The Romantic Prince.

There are three fictional jesters who one might reasonably accept as influences, however unconscious that influence, on Sabatini’s development of Kuoni the jester’s love story. Verdi’s Rigoletto had its première in 1851. The barely suppressed rage and frustration, their eruption in savage mockery, these aspects of Kuoni’s behaviour are very similar to that which appears in the jester Rigoletto. Both conceal a passionate and tender love. The operatic fool is a father, the fool in the story a lover manqué.

In 1892 Leoncavallo’s I Pagliacci introduced the now classic phrases that few people who use them know the source of: “on with the motley” (vesti la giubba) and “laugh, clown, laugh” (ridi, Pagliaccio) from Canio the clown’s famous aria. Why should not Rafael Sabatini the son of operatic singers be acquainted with these two popular operas?

He was surely familiar, too, with Dumas perè’s Chicot the Jester. Like Chicot, Kuoni appears to have been well born; his surname has the requisite particle. Very like Chicot is Kuoni’s concealment behind the curtains in the chamber where the king and his trusted council are met to plot a pre-emptive coup against traitors whose conspiracy has come to their knowledge, and Chicot-like are Kuoni’s comments on the plot he has overheard. Like Chicot, too, are Kuoni’s intelligent countermeasures, swift and decisive action, and above all his skill with the sword, not forgetting his mocking banter all through the dramatic climax of the action.

Unlike Chicot altogether, and unlike any opera I have come across so far, are the sentimental conclusion and the sacrifice of man for woman he loves, respectively. (In the operas I know it’s the other way around: woman sacrifices herself for man she loves.)

In 1894, Anthony Hope’s classic sentimental romance, The Prisoner of Zenda, was published, and in 1898 its sequel, Rupert of Hentzau. Hope (1863-1933) was certainly an influence on Sabatini, his younger contemporary. The hero of Prisoner dies, in the sequel, to save his lady’s honour. It is a conclusion made inevitable by one of the trends in Story at that period in England

When compared with the stylized , affected mode of narrative Hope adopted in some of his historical romances – as for instance in the stories published as The Heart of Princess Osra – Sabatini’s Fool’s Love Story is easier to read. The latter is narrated in the present tense, an unusual effect difficult to sustain successfully, but one which conveys a strong impression of drama – rather like a scenario for a film. As he was apt to do, Sabatini uses a number of words and constructions long outmoded, but avoids the flagrant gadzookery he sometimes lapsed into. And a few patches of dialogue either stilted or improbable in the circumstances are compensated by many exchanges with the sharp intelligence, vitality and suppleness which characterise ‘Sabatini speech’, that style of dialogue which makes his best writing such a pleasure to read.

The Fool’s Love Story is set in 1635, beginning perhaps in late June and concluding on the fateful night of August 12. It is the first of a number of stories that Sabatini places in the imaginary kingdom of Sachsenberg France

Another quirk of Sabatini’s mentioned earlier is the re-use of surnames in completely unrelated stories. King Ludwig IV, his kingdom of Sachsenberg

Jesse F. Knight, who has rescued Rafael Sabatini from unmerited obscurity, finds Fool markedly operatic in its structure and in what he calls “the grand gesture”. He wonders if Sabatini had a libretto in mind when he wrote this story. He might well have done so, for Sabatini aspired to be a playwright as well as a novelist. He met with little success in the theatre yet we cannot really know why his plays failed because only one of them was ever published. The others seem to have vanished for ever.

[to be continued]

scribendi cacoethes

LINGUISTIC LAPSES

Her parents had left Goa before she was born. They spoke often of their native land but never revisited it, and did not teach her to speak either Konkani or Portuguese. Indeed, they seldom spoke either language themselves. Nevertheless, she grew up with the dream of returning some day to the land of her forefathers.

It happened that an opportunity to visit Goa came her way, and she prepared herself for the experience. But there wasn’t much time and she never got so far as to master even her native tongue. So it was that an apprehensive young exile disembarked at Panaji on a May morning.

Instantly her ears were filled with the sound of Konkani spoken – as it seemed to her – at the speed of light, and frequently laced with a liberal dose of Portuguese words vaguely familiar to her. She was charmed by the sounds she heard but dazed by incomprehension. Giving up, she let herself be taken for a tourist.

Yet, safe in the cocoon of an expensive restaurant, she dared to try out her unfledged Konkani. Catching the eye of a waiter she addressed him with assumed confidence: “Agô!” The man was clearly startled. And she, seeing it, was just as plainly abashed. The waiter recovered first, understood, concealed his amusement and took her order. But she saw him at the service door, enjoying the joke with his colleagues. Too late, she recalled that a male is always addressed as “arê”; agô is the usage for a female.

She spent the rest of the day and much of the next trying to furbish her tiny vocabulary of Konkani and Portuguese by leafing through the local newspapers. Next afternoon she visited relatives. Coming away, she realized that she had left her sunglasses (oculos, in Portuguese) behind. So she retraced her steps, and explained to the servant who appeared at the front door that she had left her hokol (bride, in Konkani) on the coffee table.

But she is obstinate, and in defiant mood asked her cousins for the key to their village home, which they had offered her the use of. Recalling the bride on the coffee table, they thoughtfully sent ahead an elderly retainer to cook and keep house for her over the weekend.

When it was past her usual lunch time, she went into the kitchen to investigate. “Arê” (she took pride in getting it right), “mesta, tum kolo?” (Cook, are you a jackal?). Mesta looked at her with a wild surmise, but she was smiling and seemed quite normal. He grinned back nervously and replied: “Na, bai, hanv kolo noi”. She sensed she had made a mistake and retreated.

A while later, ravenously hungry, she tried again. “Mesta, tum kul’li?”(Cook, are you a crab?) Mesta took some time to reply, and eyed her anxiously as she left the kitchen.

What she was going to ask on her third foray into the kitchen he would never know. As soon as he heard her “Mesta” the old man jumped like a shot rabbit and scuttled out of the house at speed. He was taking no chances. Which was a pity because, after all, she had almost got it right this time: “tum kelo?” is a passable attempt at “have you finished?”

Ruth Heredia is the originator and

holds the copyright to all material on this blog unless credited to some

source. Please do not use it or pass it off as your own work. That is theft. If

you wish to link it, quote it, or reprint in whole or in part, please be

courteous enough to seek my permission.