Journal Jottings

BOOKWORM

[Pace, Blaise Pascal, mon ami, use of the first person singular is unavoidable here.]

“You know you‘ve read a good book when you turn the last page and feel a little as if you have lost a friend.” ~ Paul Sweeney

I have just renewed acquaintance with an ‘old’ friend, The Marquis of Carabas by Rafael Sabatini. The best of Sabatini has to be read twice over: the first time for the story & the second for the writing. The best of Sabatini’s books become friends for life.

I read Carabas a few years ago & was impelled to investigate the Quiberon expedition of 1795, to compare it minutely with Sabatini’s story. Events overtook me & the project was regretfully abandoned, unfinished. Now that investigation has been resumed & the final results will probably appear on the Rafael Sabatini website: http://www.rafaelsabatini.com/. In any case it is a site that appreciative readers of Sabatini must not miss.

--> Written many years after Scaramouche (pub. 1921), The Marquis of Carabas, also known as Master-at-Arms, is remarkably similar in many particulars. Given the time of life when Sabatini wrote Carabas, and all that had happened to him between 1921 and 1940, it is not surprising that Carabas is more subdued in tone. There is plenty of action, a deal of mystery, hatred, betrayal, duels aplenty, and much clever dialogue. Sabatini is master of that. It is a characteristic of his stories that makes a reader either embrace or spurn him. There is also a marked advance in the writing and the plotting from what Sabatini achieved in the first edition of Scaramouche. In Carabas there is such a thoughtful engagement with the complexities of history as is found in the revised edition of Scaramouche. This hero, Quentin de Morlaix, does not begin with a fixed position on who is right and who is wrong, although he has a sensibly democratic leaning from the outset. His basic values do not change but he does learn to reckon with human beings as individual persons first and 'party members' second. The novel has many characters who, like most human beings, are difficult to classify unequivocally as either friend or foe.

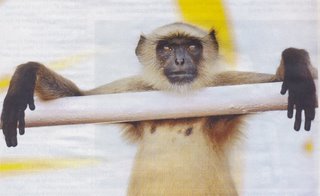

HAIR-Y

Photo: SPORTSTAR: Clive Mason/Getty Images

Intent, appraising – umpire in disguise, perhaps? Spectator at Sardar Patel Stadium, Motera, during a Champion’s Trophy match between S. Africa & Sri Lanka.

BOOKWORM

[Pace, Blaise Pascal, mon ami, use of the first person singular is unavoidable here.]

“You know you‘ve read a good book when you turn the last page and feel a little as if you have lost a friend.” ~ Paul Sweeney

I have just renewed acquaintance with an ‘old’ friend, The Marquis of Carabas by Rafael Sabatini. The best of Sabatini has to be read twice over: the first time for the story & the second for the writing. The best of Sabatini’s books become friends for life.

I read Carabas a few years ago & was impelled to investigate the Quiberon expedition of 1795, to compare it minutely with Sabatini’s story. Events overtook me & the project was regretfully abandoned, unfinished. Now that investigation has been resumed & the final results will probably appear on the Rafael Sabatini website: http://www.rafaelsabatini.com/. In any case it is a site that appreciative readers of Sabatini must not miss.

As he does in Scaramouche the King-maker (pub. 1931), Sabatini takes a byway of the history of the French Revolution. He weaves that bit of history into his tale of love and adventure and growing up, focusing on the Quiberon misadventure, and draws his hero into the historical narrative as convincingly as he does in King-maker. Again, as he does in King-maker and other novels (Bellarion, pub.1926, for instance), Sabatini takes a real historical person and gives him an important part in the plot, but he also makes a significant alteration or two in the 'history' of that person as a character in his story. This should keep an alert reader from ever confusing Sabatini's fictitious representation in the novel with the true historical person. I can imagine Sabatini's special satisfaction with this plot device since he used it more than once.

Another point of likeness with Scaramouche the King-maker is in the gradually developing relationship between the hero and his 'patron' - who is in both cases a real historical person - which ends with a rather similar transition in the hero's hitherto ambivalent feelings for this person, both transitions arising from a similar cause. The legitimacy of the hero's parentage is questioned, as it is in more than one of Sabatini's novels and short stories, including Scaramouche. (This is a characteristic of Sabatini's writing with a painful origin in his own life.) However, unlike Andre-Louis Moreau, who - at least in Scaramouche - hurtles from adventure to adventure, changing roles as he changes apparel, Quentin de Morlaix has his share of adventure but with a difference. Quentin's adventures are far more believable, more logical from the premise of the plot, and certainly bring him closer to death, time and again, than the adventures of Andre-Louis threaten his life in Scaramouche - though the case is different in King-maker.

The French Revolution seems to have had a special appeal for Sabatini. Six years before The Marquis of Carabas, he wrote Venetian Masque, whose back-story includes the Quiberon expedition, and its plot has many elements in common with the later novel: a dishonest steward, the usual clutch of tiresome emigres, a beautiful aristocratic 'spy' who tries to seduce the hero, and the blurring of national identity - is the hero fully French or is he English?

One of the characteristics of Sabatini's historical novels that particularly appeals to me is that history doesn't just become a source of 'local colour'. It is brought to life using whatever Sabatini had garnered from his wide reading of primary sources. Early in The Marquis of Carabas we are introduced to the world of French emigres in London, and I was reminded of Gone With The Wind, of the preoccupation with what was necessarily a shabby gentility in the remainder of Southern society that survived in Atlanta. Among the emigres is a nobleman to whom a nabob's daughter is married, clearly a barter of wealth for a title - shades of Vanity Fair. Except that this couple are nothing like the generally deplorable society Thackeray depicts. These are kind, generous and sensible.

The heroine is intelligent, spirited, loving - and best of all - that rara avis among Sabatini women, not liable to choose, unfailingly, a perverse interpretation of the hero's words/deeds/motives, which choice makes both miserable for unconscionably long stretches of a novel. The opening and closing sentences of the novel are also typical of Sabatini at his best, and are in a similar vein of humour (and of music) as those he wrote for Scaramouche and for Scaramouche the King-maker.

The Marquis of Carabas does become a friend one parts from regretfully.

Those who knew my father well may remember that FJ was a lifelong admirer of Sabatini’s writings. He first made their acquaintance in the mid to late 1930s, & read them with undiminished pleasure until the end of his life.

Anyone who wants to read The Marquis of Carabas online can download it for free from gutenberg.net.au.

CUISINART

Here are two recipes peculiar to the family. The recipe for sorpatel was evolved by the pater, Frederic Joseph, from the instructions of his beloved mother-in-law, Eugenia. She, in turn, either developed it herself from the traditional recipe or inherited this version from her Costa father, who was a notable ‘theoretical’ cook. Why ‘theoretical’? Because in his day he only needed to sit in a comfortable chair in the kitchen while he directed the cooks & scullions who would give substance to his idea for a dish.

The recipe for feijoada was reconstructed from memory of a version that FJ himself had conjured out of his own memories of a favourite dish. He did not leave a written note of this recipe.

Sorpatel (Costa-Heredia variant)

Pork (medium fat) 750 gms

Pig liver 250 gms

Salt

Ginger-garlic paste 1 heaped tsp

Tomato puree

Onions 3 large

Condiments:

Chilli powder 3 heaped tsps

Dhaniya (coriander) powder 2 heaped tsps

Geera (cumin seed) powder 1 heaped tsp

Haldi (turmeric) powder ½ tsp

Spices:

Cinnamon ]

Cloves ] all 3 ground together to make 1 tbsp

Cardamom ]

Hot water

Vinegar

Gur (jaggery)

Setting aside a few pieces of fat, cut pork & liver into smallish pieces.

Marinate the meat with salt, ginger-garlic paste & tomato puree.

Render fat from pieces set aside. Remove the chitterlings, drain & add to the marinating meat.

In a pressure cooker fry thinly sliced onions in the rendered lard until pearly.

Add the condiments & roast well on medium heat.

Add the meat & brown it thoroughly, reducing the heat to allow juices to flow out of the browning meat. To further this process, cover the pan (but not with its proper lid) after stirring in the spoonful of ground spices.

Rinse out with hot water the pan used for marinating, & add this water to the meat. (Water added to cooking meat must ALWAYS be hot, else the meat becomes tough.)

Close the pressure cooker with its proper lid; increase the heat till steam comes out of the vent; fit the weight on; reduce the heat after the first expulsion of steam; & cook the meat for 35 minutes thereafter.

After the cooker is cool enough to open, add vinegar & gur to taste. Adjust seasoning if necessary, & boil briskly for a short while to cause free floating lard to be absorbed in the gravy. (Don’t ask how & why this works. FJ used to do it, & taught the method. It works.)

Feijoada (FJ’s version)

Rajma (red kidney) beans

Chicken soup cube

Pork 250 gms

Salt

Oil

Onion 1 medium-size, finely sliced

Condiments:

Haldi

Geera

Dhaniya

Chilli

Spices:

Star anise 1

Cloves a few coarsely ground with the star anise

Ginger-garlic paste 1 heaped tsp

Dried red chillies 2

Tomato puree

Hot water

Balsamic vinegar

Gur

Cut the pork into medium size chunks & salt it.

Pressure cook the beans, drain them, & stir in the soup cube while the drained beans are still hot, so that it dissolves.

Fry the onion till pearly.

Add condiments & spices & fry well.

Add the G&G paste & the chillies.

Brown the pork thoroughly & then reduce the heat to draw out juices.

Add tomato puree & then the beans, with sufficient hot water to cover pork & beans while they simmer under cover.

It may be necessary to top up with more hot water to make enough gravy.

When the pork is judged to be soft enough, add vinegar & gur to taste.

Ruth Heredia is the originator and

holds the copyright to all material on this blog unless credited to some

source. Please do not use it or pass it off as your own work. That is theft. If

you wish to link it, quote it, or reprint in whole or in part, please be

courteous enough to seek my permission.

No comments:

Post a Comment