scribendi cacoethes

It was during the Divali vacation of 1967 that the family travelled to Delhi, the three children on their first visit. Treats were treats in that bygone time; each child had saved up pocket money earned by doing household chores. The money was for souvenirs of those wondrous cities, Delhi & Agra, laden with so much history.

The elder girl, just turned sixteen, was by nature poised between the practical & the romantic. Not long since, a veritable Aladdin’s cave of a shop had opened in Delhi: the Central Cottage Industries Emporium, down a shabby lane leading off Janpath. The father, a civil servant working for what was then a miserly wage, had once or twice ventured in & come home with small but memorable treasures such as he could afford. All three children knew what they wanted to spend their tiny fortunes on, & at the Emporium the eldest carefully laid out her thirty rupees on things both useful & pleasing.

Next day the family went on a tour of historic Delhi. On their way into the Red Fort they entered Chatta Chowk or Meena Bazaar, a covered alley lined with rather shabby little curio shops, most containing fairly crude souvenirs for a tourist trade then only just beginning. There were reproductions of Moghul miniatures & Kishangarh paintings, of a clumsy execution & garish colouring that were apparent even to the relatively uneducated eye of the 16-year-old.

Next day the family went on a tour of historic Delhi. On their way into the Red Fort they entered Chatta Chowk or Meena Bazaar, a covered alley lined with rather shabby little curio shops, most containing fairly crude souvenirs for a tourist trade then only just beginning. There were reproductions of Moghul miniatures & Kishangarh paintings, of a clumsy execution & garish colouring that were apparent even to the relatively uneducated eye of the 16-year-old.

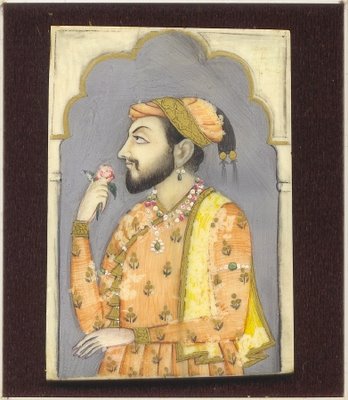

Only one shop had pieces that seemed nearer the real thing, & into it the father led the way, but without displaying any noticeable enthusiasm. He directed his family’s attention to this & that, then casually asked the shopkeeper if he had any old paintings on ivory. (This was before the ivory trade had become a forbidden activity.) The man seemed to consider before, with a movement equally casual, he leaned down to a drawer & brought out a small ramshackle cardboard box. From it he extracted an object wrapped in a roughly torn scrap of brown paper. It was a portrait of a man, in profile, apparently painted on a rectangle of ivory.

Some of the paint was already rubbed off, & the shopkeeper – oh, the monster – rubbed his thumb reflectively over what remained saying, “Is this the kind of painting you want, Sahib?”

Some of the paint was already rubbed off, & the shopkeeper – oh, the monster – rubbed his thumb reflectively over what remained saying, “Is this the kind of painting you want, Sahib?”

Indifferently, the father took it & carried it over to what little light came in at the door. “Yes, something like this. But this is not in very good condition. Have you any others?”

“No, Sahib. Only this one. But there are others” – pointing to the reproductions – “which are nice & new.”

“How much is this old one?”

“Thirty rupees, Sahib.”

“Do you want it?” The father had turned to the girl.

“Thirty rupees”, exclaimed the mother, “that’s far too much.” And looking doubtfully at her daughter, “Anyway why do you want it? You’ve already spent all your money.”

The father continued to look at the slightly bewildered girl. He seemed intent on conveying something more than his words indicated, but what it was she could not guess.

“You wanted a souvenir of Delhi. This looks like a suitable one. If you want it, I’ll lend you the money. You can pay it back when you’ve earned some more”, he said, quelling his wife’s protest with a glance.

The girl never quite knew why she did it. To please her father? Perhaps. Or because it was an adventure; such a grown-up thing to spend a small fortune on an object which she partly recognized as ‘art’ & as ‘history’, but partly doubted the value of, seeing how shabby it was. “Yes,” she replied, and “Thank you.”

Her father counted out the money while the miniature disappeared once more into its unworthy casings. “Here, take your souvenir & keep it safe. It must be the most valuable thing you’ve ever bought.” He was pleased.

The mother continued to protest: “At least you could have bargained.”

Months passed. One day the father said: “Mr N will be dropping in this evening. We have some work.” (Mr N was a government official.) “Give him a nice hot cup of tea & some biscuits. After that you can show him your miniature. I told him about it. He is a numismatist but he knows quite a lot about antiques in general.”

So the little painting was brought out, now housed less unworthily in a jeweller’s box. Mr N examined it closely, asking for a magnifying glass & holding the ivory rectangle up to the light.

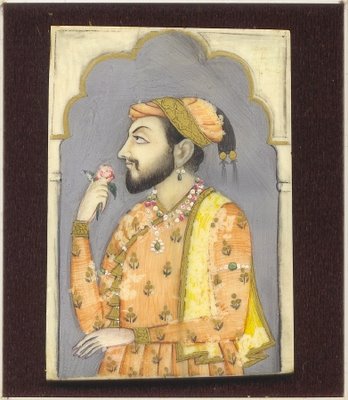

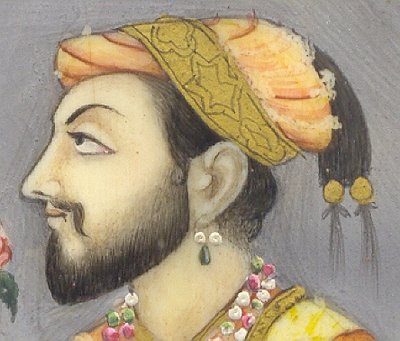

“I don’t know much about these things – you should show it to an expert. But to me this appears to be a genuine miniature, probably dating to the reign of Aurangzeb. See the flat turban jutting out behind the head: that was the style in Aurangzeb’s time. Quite different from fashions in Shah Jahan’s court. This is a prince.”

“Why do you say, ‘a prince’?”

“Why do you say, ‘a prince’?”

“There were strict rules about dress at the court. A man could wear jewels only according to his status. A mansabdari was only allowed to wear jewels according to the size of his mansab; maybe pearls with rubies or pearls with emeralds, but not all three such costly gems together. Only princes could wear all these.”

“Ah, a sumptuary law. And what about the genuineness---?”

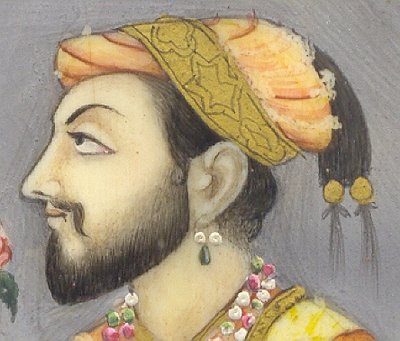

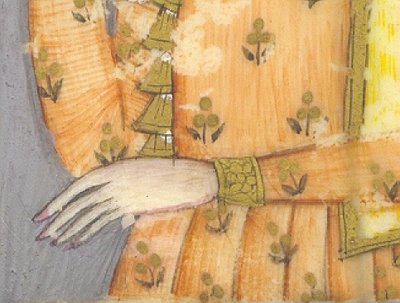

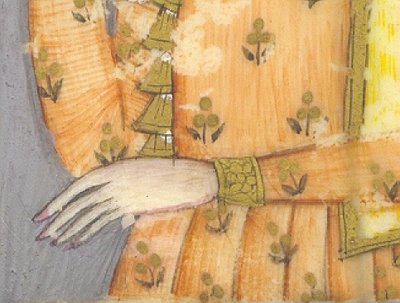

Mr N smiled & picked up the magnifying glass. “Look at the beard” he said. “Each hair is a separate stroke. It was made with a brush having a single hair in it. And look at the henna on his hands & the reddish colour in the corner of his eye. A modern painter who makes copies does not have the patience to do such work.” He was quite carried away.

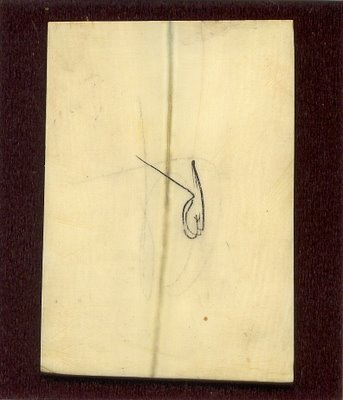

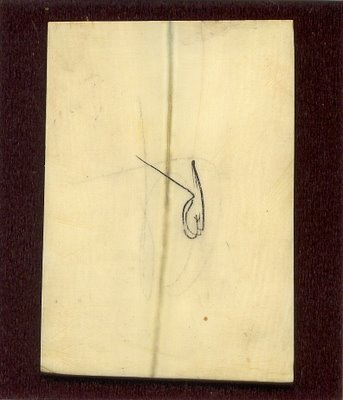

“See the line running through the ivory – you must look at the reverse of the painting. This proves it is a piece of real ivory; not a piece of bone. That mark in black paint is a letter. It is the painter’s initial.”

“See the line running through the ivory – you must look at the reverse of the painting. This proves it is a piece of real ivory; not a piece of bone. That mark in black paint is a letter. It is the painter’s initial.”

He paused, & repeated his earlier caution: “Still, you should show it to an expert.”

The father ignored this. “How much would you say it was worth?”

Again Mr N smiled. “If it was gold or gems I could tell you the worth. But something like this is worth only as much as anyone thinks it is worth. There is no intrinsic value. If you want it, it has value. If you are not interested, it is valueless. How much did you pay for it, may I ask?”

He was still studying the miniature as he spoke & did not notice that the father had silenced the girl with a look.

“Three hundred rupees” said the father. “She paid three hundred for it.”

“Really?” Mr N looked up, impressed. “Well, young lady, I would say you got a bargain in that case.”

Then the men resumed their discussion while the girl, having returned thanks somewhat mechanically, gathered up her belongings & went off to reflect on all she had heard.

Later, the father came away from ushering his visitor out. He was jubilant.

“Didn’t I tell you? Let this be a lesson to you. When you see a thing that is worthwhile, don’t bargain. If you can’t afford it, walk away without regrets, happy that you saw it. It is clearly not meant for you. But if you can afford it, even by sacrificing something else you could have, buy it without bargaining. It is worth the value you set on it.

“But, that apart, I think you are very lucky to have got this miniature – a genuine antique – so cheap”, said he, forgetting that it was his discerning eye & educated taste which had brought about the translation of a prince’s portrait into the pocket of a pauper.

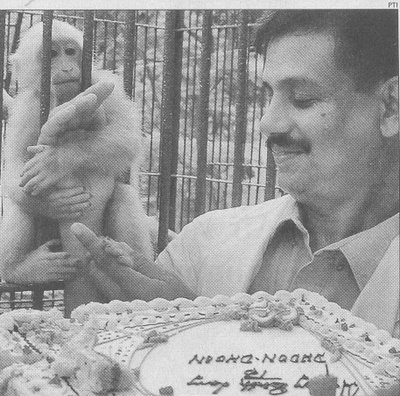

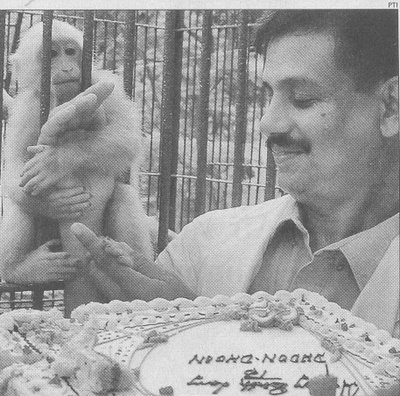

~ "Dhoon-Dhoon, a stump-tailed macaque, celebrates her first birthday at Assam State Zoo in Guwahati. The macaque, raised by zoo-keepers after she lost her mother in infancy, belongs to an endangered species."

She can’t eat the cake, but what satisfaction on her face, & what a look of affectionate absorption on the man’s, not to mention her embrace of his softly curved hand! Delightful & rare treat in the morning papers otherwise full of dreary stuff.

SEEKING

Can anyone find a source for the following line, even with a changed word here or there?

'Proud Agamemnon trod on purple to the axe behind the door.'

Could it be by W H Auden?

Or from a translation of a Greek play by any of the immortal trio: Aeschylus, Euripides or Sophocles?

It is important to find out whether this line, found on a sheet of paper tucked into the writer's file of ideas & notes & pieces left incomplete, is just another 'idea' or if it is a quotation carelessly copied without attribution.

INCOGNITO or a Prince and a Pauper

It was during the Divali vacation of 1967 that the family travelled to Delhi, the three children on their first visit. Treats were treats in that bygone time; each child had saved up pocket money earned by doing household chores. The money was for souvenirs of those wondrous cities, Delhi & Agra, laden with so much history.

The elder girl, just turned sixteen, was by nature poised between the practical & the romantic. Not long since, a veritable Aladdin’s cave of a shop had opened in Delhi: the Central Cottage Industries Emporium, down a shabby lane leading off Janpath. The father, a civil servant working for what was then a miserly wage, had once or twice ventured in & come home with small but memorable treasures such as he could afford. All three children knew what they wanted to spend their tiny fortunes on, & at the Emporium the eldest carefully laid out her thirty rupees on things both useful & pleasing.

Next day the family went on a tour of historic Delhi. On their way into the Red Fort they entered Chatta Chowk or Meena Bazaar, a covered alley lined with rather shabby little curio shops, most containing fairly crude souvenirs for a tourist trade then only just beginning. There were reproductions of Moghul miniatures & Kishangarh paintings, of a clumsy execution & garish colouring that were apparent even to the relatively uneducated eye of the 16-year-old.

Next day the family went on a tour of historic Delhi. On their way into the Red Fort they entered Chatta Chowk or Meena Bazaar, a covered alley lined with rather shabby little curio shops, most containing fairly crude souvenirs for a tourist trade then only just beginning. There were reproductions of Moghul miniatures & Kishangarh paintings, of a clumsy execution & garish colouring that were apparent even to the relatively uneducated eye of the 16-year-old.Only one shop had pieces that seemed nearer the real thing, & into it the father led the way, but without displaying any noticeable enthusiasm. He directed his family’s attention to this & that, then casually asked the shopkeeper if he had any old paintings on ivory. (This was before the ivory trade had become a forbidden activity.) The man seemed to consider before, with a movement equally casual, he leaned down to a drawer & brought out a small ramshackle cardboard box. From it he extracted an object wrapped in a roughly torn scrap of brown paper. It was a portrait of a man, in profile, apparently painted on a rectangle of ivory.

Some of the paint was already rubbed off, & the shopkeeper – oh, the monster – rubbed his thumb reflectively over what remained saying, “Is this the kind of painting you want, Sahib?”

Some of the paint was already rubbed off, & the shopkeeper – oh, the monster – rubbed his thumb reflectively over what remained saying, “Is this the kind of painting you want, Sahib?”Indifferently, the father took it & carried it over to what little light came in at the door. “Yes, something like this. But this is not in very good condition. Have you any others?”

“No, Sahib. Only this one. But there are others” – pointing to the reproductions – “which are nice & new.”

“How much is this old one?”

“Thirty rupees, Sahib.”

“Do you want it?” The father had turned to the girl.

“Thirty rupees”, exclaimed the mother, “that’s far too much.” And looking doubtfully at her daughter, “Anyway why do you want it? You’ve already spent all your money.”

The father continued to look at the slightly bewildered girl. He seemed intent on conveying something more than his words indicated, but what it was she could not guess.

“You wanted a souvenir of Delhi. This looks like a suitable one. If you want it, I’ll lend you the money. You can pay it back when you’ve earned some more”, he said, quelling his wife’s protest with a glance.

The girl never quite knew why she did it. To please her father? Perhaps. Or because it was an adventure; such a grown-up thing to spend a small fortune on an object which she partly recognized as ‘art’ & as ‘history’, but partly doubted the value of, seeing how shabby it was. “Yes,” she replied, and “Thank you.”

Her father counted out the money while the miniature disappeared once more into its unworthy casings. “Here, take your souvenir & keep it safe. It must be the most valuable thing you’ve ever bought.” He was pleased.

The mother continued to protest: “At least you could have bargained.”

But the father told his daughter, in the manner of a Polonius dispensing advice, “Bargaining only cheapens a thing, lessens its value in your own mind.”

So the little painting was brought out, now housed less unworthily in a jeweller’s box. Mr N examined it closely, asking for a magnifying glass & holding the ivory rectangle up to the light.

“I don’t know much about these things – you should show it to an expert. But to me this appears to be a genuine miniature, probably dating to the reign of Aurangzeb. See the flat turban jutting out behind the head: that was the style in Aurangzeb’s time. Quite different from fashions in Shah Jahan’s court. This is a prince.”

“Why do you say, ‘a prince’?”

“Why do you say, ‘a prince’?”“There were strict rules about dress at the court. A man could wear jewels only according to his status. A mansabdari was only allowed to wear jewels according to the size of his mansab; maybe pearls with rubies or pearls with emeralds, but not all three such costly gems together. Only princes could wear all these.”

“Ah, a sumptuary law. And what about the genuineness---?”

Mr N smiled & picked up the magnifying glass. “Look at the beard” he said. “Each hair is a separate stroke. It was made with a brush having a single hair in it. And look at the henna on his hands & the reddish colour in the corner of his eye. A modern painter who makes copies does not have the patience to do such work.” He was quite carried away.

“See the line running through the ivory – you must look at the reverse of the painting. This proves it is a piece of real ivory; not a piece of bone. That mark in black paint is a letter. It is the painter’s initial.”

“See the line running through the ivory – you must look at the reverse of the painting. This proves it is a piece of real ivory; not a piece of bone. That mark in black paint is a letter. It is the painter’s initial.”

He paused, & repeated his earlier caution: “Still, you should show it to an expert.”

The father ignored this. “How much would you say it was worth?”

Again Mr N smiled. “If it was gold or gems I could tell you the worth. But something like this is worth only as much as anyone thinks it is worth. There is no intrinsic value. If you want it, it has value. If you are not interested, it is valueless. How much did you pay for it, may I ask?”

He was still studying the miniature as he spoke & did not notice that the father had silenced the girl with a look.

“Three hundred rupees” said the father. “She paid three hundred for it.”

“Really?” Mr N looked up, impressed. “Well, young lady, I would say you got a bargain in that case.”

Then the men resumed their discussion while the girl, having returned thanks somewhat mechanically, gathered up her belongings & went off to reflect on all she had heard.

Later, the father came away from ushering his visitor out. He was jubilant.

“Didn’t I tell you? Let this be a lesson to you. When you see a thing that is worthwhile, don’t bargain. If you can’t afford it, walk away without regrets, happy that you saw it. It is clearly not meant for you. But if you can afford it, even by sacrificing something else you could have, buy it without bargaining. It is worth the value you set on it.

“But, that apart, I think you are very lucky to have got this miniature – a genuine antique – so cheap”, said he, forgetting that it was his discerning eye & educated taste which had brought about the translation of a prince’s portrait into the pocket of a pauper.

Journal Jottings

~ "Dhoon-Dhoon, a stump-tailed macaque, celebrates her first birthday at Assam State Zoo in Guwahati. The macaque, raised by zoo-keepers after she lost her mother in infancy, belongs to an endangered species."

She can’t eat the cake, but what satisfaction on her face, & what a look of affectionate absorption on the man’s, not to mention her embrace of his softly curved hand! Delightful & rare treat in the morning papers otherwise full of dreary stuff.

SEEKING

Can anyone find a source for the following line, even with a changed word here or there?

'Proud Agamemnon trod on purple to the axe behind the door.'

Could it be by W H Auden?

Or from a translation of a Greek play by any of the immortal trio: Aeschylus, Euripides or Sophocles?

It is important to find out whether this line, found on a sheet of paper tucked into the writer's file of ideas & notes & pieces left incomplete, is just another 'idea' or if it is a quotation carelessly copied without attribution.

Ruth Heredia is the originator and

holds the copyright to all material on this blog unless credited to some

source. Please do not use it or pass it off as your own work. That is theft. If

you wish to link it, quote it, or reprint in whole or in part, please be

courteous enough to seek my permission.

1 comment:

Found the source, or rather what had been read long before, and was dimly remembered, which caused me to doubt that the line was an idea of my own - one which led to the writing of my poem titled HUBRIS. W.H. Auden edited the (Viking) Portable Greek Reader in which he had selected a translation of Agamemnon by Aeschylus made by W.G. Headlam & G. Thomson. There, in line 927, appears this phrase in Agamemnon's exchange with Clytemnestra: "trod the purple".

Post a Comment